Home

+

Published : 04 May 2025, 03:08 AM

Fears of famine in Myanmar’s Rakhine have led the interim government to approve, “in principle”, the opening of a United Nations-backed humanitarian corridor for emergency aid—sparking controversy and opposition.

The government has yet to clarify how or where the corridor would be established, though it has floated possible conditions for its operation.

In the face of clear objection from the BNP and some other political parties, the government has said if the UN confirms the move, the final decision will involve “consultation with everyone”.

Experts are also divided in their opinions about Bangladesh’s involvement in the aid passage as some label it a threat to “independence and sovereignty”.

They say the consent of the Myanmar government is a priority over everything else if Bangladesh is to involve itself in the establishment of the said corridor for legal obligations.

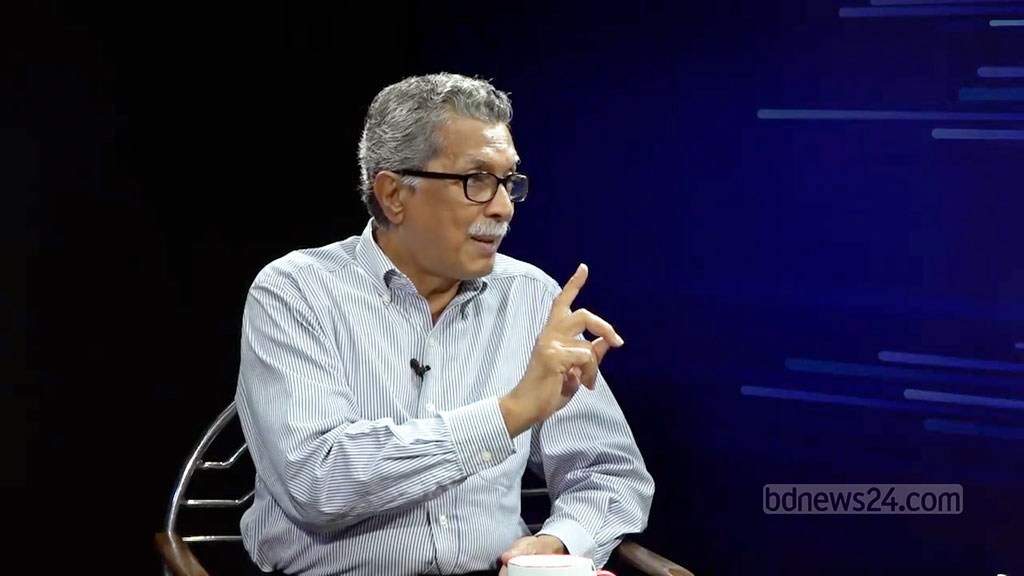

Security analyst retired major general ANM Muniruzzaman has underscored the need for Myanmar’s consent in establishing a UN-backed humanitarian corridor into Rakhine, warning of legal and security risks.

“There has been no consent from the Myanmar government to our knowledge,” said Muniruzzaman, president of the Bangladesh Institute of Peace and Security Studies (BIPSS).

“Crossing their border and entering their territory without consent would violate their sovereignty and be entirely illegal under international law.”

He pointed to the complex dynamics in Rakhine, involving both Myanmar’s junta government and the Arakan Army, the armed group controlling much of the region.

Highlighting the involvement of China, Russia, and India in the broader Myanmar conflict, Muniruzzaman called the issue “a matter of national security” and “a highly sensitive state decision”.

His position was unequivocal: “If it’s not legal, it shouldn’t be done.”

Even if Myanmar grants consent, he stressed that any decision should follow parliamentary discussion or political consensus.

“If this must be done at some point, the decision must go through the parliament,” he said. “Since parliament is currently absent or inactive, such a decision should only proceed after dialogue with major political parties and their consent. It would be inappropriate for the interim government alone to decide.”

Former ambassador M Humayun Kabir echoed the need for caution, noting that Bangladesh would still require “some kind of permission” from Myanmar to proceed.

“The Myanmar government has to convince you [the government] that sending aid through the corridor would be beneficial. The Arakan Army has added a new element to the two-state issue. You can only open it if the Arakan Army and the Myanmar government agree. Because it is not something only you can decide.”

Noting that the details are not clear, Humayun, president of the Bangladesh Enterprise Institute, said: “The United Nations has requested Bangladesh. In fact, there has been a discussion between Bangladesh and the United Nations.

“But have we or the United Nations spoken about it to the Myanmar government or the Arakan Army? Or else, two parts of a quadrilateral [agreement] are missing, all four must come together. Is there any opportunity for those four to be together? Have we explored these? We have to think about these issues before we make a decision.”

SPOTLIGHT ON HUMANITARIAN CORRIDOR

Myanmar, Bangladesh's neighbour to the east, has been ravaged by a war between the military junta government and rebel forces since 2021. In December last year, the Arakan Army took over the entire Rakhine state adjacent to Bangladesh. The military junta has only been able to maintain control of the Kyaukphyu Deep Sea Port in the state.

In November, in the thick of the war in Rakhine, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) published a report titled 'Rakhine: A Famine in the Making'.

The report said that Rakhine is under threat of imminent famine. It is estimated that local food production will only be able to meet the needs of 20 percent of the population in March-April 2025. Rice production is declining as people stay away from agricultural work due to a lack of seeds and fertilisers, adverse weather, and displacement. About two million people are at risk of starvation due to the almost complete shutdown of trade.

The report said that the Arakan Army controls the territory of Rakhine. However, the only seaport along the entrance to Rakhine is occupied by the junta. As a result, the entry of domestic and international goods into Rakhine is closed.

Oppressive financial meltdown, crippling inflation, drastic reduction in income and local food production contributed to the present situation of Rakhine.

In the midst of the turmoil, on Apr 8, after UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres' trip to Dhaka, Khalilur Rahman, the High Representative for the Rohingya Crisis and Priority Issues, talked about the idea of a 'humanitarian assistance channel' in Bangladesh.

Noting that the notion of Bangladesh's involvement in establishing an aid channel was coined in discussions with Guterres in New York on Feb 7, he said at a press conference that day that he went to the UN secretary-general after discussing with everyone - the Arakan Army, international organisations and the Myanmar junta.

"We told him that there is no alternative to international assistance to address the humanitarian crisis in Rakhine. That work will be done under the supervision of the UN.”

Almost three weeks after Khalilur’s statement, Foreign Advisor Touhid Hossain said on Sunday that the government had taken an 'in-principle decision' to open up a “humanitarian corridor”.

In response to a question at the Foreign Ministry, he said: "I can tell you this much, in principle we agree to it. Because there will be humanitarian passage.

"But we have some conditions for it. I will not go into details, but if those conditions are met, we will definitely cooperate in it, under the supervision of the United Nations of course."

His statement sparked a debate in the political arena as parties opposed the decision which came “without any discussion”.

BNP Secretary General Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir has commented that the decision will put the country's “independence and sovereignty” at risk.

The party’s Acting Chairman Tarique Rahman said that such a decision must come from the people, from the parliament elected directly by the people.

In the face of such opposition from the parties, Chief Advisor’s Press Secretary Shafiqul Alam said on Tuesday that the government had no discussions with the “United Nations or any other organisation” to provide an aid corridor into Rakhine.

In a Facebook post, he wrote: “If the UN-led initiative is taken to provide humanitarian assistance to Rakhine State, Bangladesh will be ready to provide logical infrastructural support.”

In a message on Wednesday, the UN’s Dhaka office said if it moves to create a path for humanitarian assistance to Rakhine, permissions of both the Bangladesh and Myanmar governments would be required.

On Friday, Shafiqul said in Chattogram: “We agree to the humanitarian corridor if the UN takes the initiative. This whole thing will be done by talking to the two countries.

“When the UN begins work, it will talk to the relevant parties, the Myanmar government and us. Only then will they come to a decision.”

CONDITIONS SET BY BANGLADESH

The Bangladesh government has set several conditions for the establishment of a “humanitarian corridor”, including the creation of a conducive environment in Rakhine and the non-discriminatory and unconditional distribution of aid.

Officials from the foreign ministry said unless a favourable environment is ensured in Rakhine for transporting and distributing aid, relief operations may be hampered.

For this, either a ceasefire or a mechanism must be in place to prevent any disruption to the UN-facilitated relief operations originating from Bangladesh.

Bangladesh has also emphasised the need to ensure that aid reaches the Arakanese, Rohingya, and other ethnic minorities in Rakhine without discrimination.

The goal is to prevent any group from being deprived of assistance due to control by the Arakan Army in certain areas.

Reiterating the importance of "unconditional aid delivery”, one official said Bangladesh does not want any prerequisite conditions for receiving relief.

“No one should be told they will only receive aid if they do or do not perform a particular task,” he added.

The ministry's Myanmar Wing has also indicated that the humanitarian corridor initiative is being considered in light of a looming famine in Rakhine, which could trigger a new influx of refugees into Bangladesh.

More than 750,000 Rohingya fled Myanmar’s Rakhine State and sought refuge in Bangladesh after Aug 25, 2017, in the wake of a military crackdown.

They joined an estimated 400,000 others already sheltering in overcrowded camps near Cox’s Bazar, a coastal district where one of the world’s largest refugee settlements now exists.

In April, Myanmar claimed to have verified 180,000 Rohingya from a list of 800,000 as eligible for repatriation.

During the same period, over 100,000 more Rohingya reportedly entered Bangladesh.

WHAT IS A ‘HUMANITARIAN CORRIDOR', HOW DOES IT WORK?

International law does not offer a definitive legal definition of a "humanitarian corridor", but it does require all parties in a conflict to ensure rapid and unimpeded delivery of humanitarian aid to civilians.

Aid workers must also be granted safe and independent access.

According to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), a humanitarian corridor is “an agreement between parties to an armed conflict that allows for safe passage in a specific geographic area for a defined time.

“These corridors facilitate the movement of civilians, the delivery of humanitarian aid, and the evacuation of the wounded or deceased.

The design and operational procedures of such corridors are determined by the involved parties.

One of the most widely known corridors was the Lachin Corridor, which connected Armenia to Nagorno-Karabakh, a region largely populated by ethnic Armenians but located within Azerbaijan’s territory.

Following the first Armenia-Azerbaijan war in 1989, the corridor was opened with Russian peacekeepers deployed to secure it.

During the 2020 war, Azerbaijani forces seized control of the Lachin Corridor.

Although it initially operated smoothly, it later became a source of dispute. Azerbaijan accused Armenia of using the corridor for illegal military supplies and natural resource transport, eventually leading to its closure. Armenia and others denied the allegations.

In 2023, Azerbaijan took full control of Nagorno-Karabakh, prompting mass displacement of its residents—many fled through the Lachin Corridor to Armenia and elsewhere.

During the Bosnian War, the United Nations declared several “safe areas” in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1993, including the Srebrenica enclave, based on two Security Council resolutions.

These areas were placed under the protection of UN peacekeepers.

The safe area concept later became one of the most controversial decisions of that war.

The UN resolutions lacked clarity on how to ensure the safety of the designated zones, leading to serious complications.

Many countries that supported the resolutions failed to take adequate action to protect civilians, reportedly due to political reasons. By 1995, conditions in the safe areas deteriorated, culminating in the Srebrenica massacre—the deadliest atrocity in Europe since World War II.

HOW RISKY IS A 'HUMANITARIAN CORRIDOR'?

If Myanmar does not grant permission for the proposed "humanitarian corridor", any entry into its territory would be deemed illegal under international law, warns security analyst retired maj gen Muniruzzaman.

The BIPSS chief pointed out that no clear information has been provided on how the corridor will be established, who will operate it, or who will ensure its security.

He cautioned that if Bangladeshi troops are tasked with securing the corridor, they could face significant risks.

“This won’t only threaten our soldiers’ safety, it will be a national security concern,” Muniruzzaman said.

He further warned that such an initiative could place Bangladesh in opposition to the interests of major powers and potentially drag the country into a proxy war—an outcome that would contradict national interests.

Muniruzzaman said, “If we pursue such actions now, in the future others might cite this precedent to justify setting up corridors inside Bangladesh. For example, if someone claims certain groups in the Chittagong Hill Tracts are under threat and seeks to create a corridor to help them, we would face a highly vulnerable situation.”

He explained that managing a corridor of this nature requires extensive resources and not only ground security but also air defence capabilities—making the operation highly complex and costly.

“Myanmar is a recognised state, and crossing its borders based solely on agreement with a non-state actor would be illegal,” he said. “We maintain formal relations with the Myanmar state, and unless it consents, any such operation would be a breach of sovereignty.”

On communication with the Arakan Army, Muniruzzaman said it would be inappropriate for the state to engage directly with non-state actors, there could be low-level coordination. “This coordination would not be at the state level. For instance, our [Border Guard Bangladesh] might handle it, but the government should not be directly involved,” he noted.

Former ambassador Humayun Kabir suggested testing the concept of a humanitarian corridor but highlighted the need for deeper consideration before implementation. “Myanmar is in a state of conflict. If we are to operate there, we must ensure we have the required skills and clear transparency in our approach.

“I am not entirely confident that we have that capacity.”

He also noted that the Myanmar government would need to approve the operation due to its territorial control.

“Since we recognise Myanmar’s borders, any activity without their consent would be illegal,” Humayun said.

Regarding the blockade of food aid to the region by the Myanmar government, he said:"Myanmar sees the Arakan Army as a terrorist organisation, which complicates humanitarian efforts."

He acknowledged that, diplomatically, a humanitarian corridor could be a "possible" solution, but emphasised that political action was equally critical. “The political dynamics have not been sufficiently addressed, which is why we’re facing these challenges today.

“If domestic political parties do not support it, how can we proceed?” he questioned.

The former ambassador also noted the complexity of working with both the Myanmar government and the Arakan Army. “Do we have that capacity? Do we have the experience and political capital to manage such a strategy?”

Humayun expressed doubt about the caretaker administration’s ability to pursue the humanitarian corridor initiative, considering the extensive time and effort required.

“Given the political context, the interim government’s responsibility for internal issues, and its focus on other tasks, it remains unclear whether this initiative can be fully realised

“As this issue is now being discussed at different levels, efforts must be made to determine the way forward based on those talks,” he concluded.

[Writing in English by Syed Mahmud Onindo and Sheikh Fariha Bristy]